Three hundred and seventy-seven pages of perceptive brilliance cannot be easily handled by all writers. Well, most readers too would stumble and fall in their inability to get a firm hold on all the nuances that the pages overturn on you mercilessly. I loved the experience. But then I have my own reasons to love this book… and not every reader may share my enthusiasm for the things that I was able to relate with.

Mohammed Hanif (born in Okara in 1964) got his commission into the Pakistan Air Force and gives us a rather intimate view of how things happen or don’t happen in the Academy there. This book rolls ahead on the rushing skateboard of fiction with Hanif standing akimbo as a cadet in the Pakistan Air Force academy… and I simply fell in love with his narrative, partly because I too spent two years in the Indian Military Academy and know the real story of every Gentleman Cadet there.

It is JUO (Junior Under Officer) Ali Shigri who is the main protagonist and we get a peep into the wit, satire, and the utterly comic situations that revolve around the drill square and the life of cadets in the Academy. The Pakistan Air Force Academy has its own share of cadets who ‘have the loudest voice, the one with the clearest throat, the one whose chest can expand to produce a command that stuns the morning crows…’ and, therefore, ‘noise is the first thing you learn to defend yourself against, and as an officer noise is the first weapon of attack that you learn to use.’

Hanif is obviously writing about a country that is inundated with a cacophony of varied noises that include the discordant ones coming from within and from outside. The noises include the ones they themselves produce to attract attention and the ones that the others like the Taliban and the fundamentalists produce to let themselves be heard in this decibel mêlée. Any intuitive writer will then appreciate and say that ‘a drill without commands is an art. When you deliver a command at the top of your voice, only the boys in your squadron listen. But when your inner cadence whispers, the gods take notice.’ No wonder then that the writer probably has an unexpressed wish that his country attempts to learn from these ‘subsonic drill techniques’ though this isn’t the only reason why the story includes Ali Shigri and his silent drill squad. They are there because Shigri needs to avenge his father’s suicide and is planning to assassinate Zia on the day he and his squad get to demonstrate this technique taught by Bannon… and if I were asked to sum up the entire plot in one paragraph I’d say the book begins with Shigri addressing the reader: he was the only one who was able to activate his assassination plan on that fateful day and then be able to walk away without being harmed. The reader is then sent back into ‘the past for most of the rest of the book, going back and forth from General Zia to Shigri, until all culminates in a pleasing final chapter…’ as one reviewer points out.

Robert Macfarlane writes in NYT that the subject of assassination has been adopted by novelists earlier and Mohammed Hanif shifts the focus eastwards to Pakistan where he ‘extends this tradition of assassination fiction and shifts it east to Pakistan. The death at its center is that of Gen. Muhammad Zia ul-Haq, president of Pakistan from 1978 to 1988.’ The questions that are raised after the Pak One explodes midway are the ones that the author tries to explore by creating characters like the blind woman and her curses, mechanical failure, human error, CIA, ISI, RAW, unhappy Generals, or simply the cases of mangoes gifted by the All Pakistan Mango Farmers Cooperative… the resultant text and the story meanders, like alcohol, through a reader’s ‘liver,… and starts to make a tunnel in his oesophagus and keeps moving up and up.’

The intrigue surrounding the death of the General and his entourage that fateful day is what Hanif is trying to explore through a work of fiction. He himself wonders and debates on who is most likely to be capable enough and powerful enough to plan and implement that plan. We get a whiff of the way minds are working in a discussion between Obaid and Ali Shigri:

‘We were General Akhtar’s suspects, General Beg will find his own,’

‘What if they actually liked my plan?’ I say, draining the last dregs from the bottle. ‘What if they just wanted to see if I could carry it out?’

‘Are you saying that the people who are supposed to protect him are trying to kill him? Are they setting free people like us? Are you drunk? The army itself?’

‘Who else can do it, Baby O? Do you think these bloody civilians can do it?’

Hanif allows us an intimate peep into the psychological state of the people of Pakistan and those who were associated with the country because of their official status and compulsions.

What I really like about Hanif is that he has a lot of varied experiences in real life – from being in the Air Force Academy to being a real time pilot then jumping to adopt journalism and becoming the head of BBC’s Urdu Service in London, and finally diving into full-time writing.

Yesh Prabhu, author of ‘The Beech Tree’ says in a review that Hanif gives us a brand of prose that is ‘spare but lucid. Even though it lacks the grandeur and splendor of Yann Martel’s or Salman Rushdie’s prose, it is spontaneous and highly readable…‘

Chandak Sengoopta has summed up his intuitive analysis of the book as being ‘a series of darkly comic vignettes about the investigation of Obaid’s disappearance and the preoccupations of General Zia and his generals. There are sharply observed sketches of toadying ministers, mindlessly efficient security chiefs, filthy prison cells, sex-mad Arab sheikhs and erudite communist prisoners (who hate Maoists more than mullahs). Zia’s limited intelligence and unlimited paranoia are portrayed with great glee.‘

The writer takes the story not just through life in the Air Force Academy, but also steps out and goes right into the centre of civilian life as it existed then… and the incident where the police constable attempts to intimidate Zia, the General, and makes some telling comments on the way his country is being run. The portrayal of the General himself shows what command the writer has over a comic vein:

Without his uniform and presidential paraphernalia, General Zia seemed to have shrunk. His silk gown floated about him. His moustache, always waxed and twirled, drooped over his upper lip. He was sucking it nervously. His hair, always oiled and parted down the middle, was in a state of disarray, like a parade squad on tea-break.

Hanif has a rather unconventional way of bringing alive his characters. He tells us about Zia in the prologue of the book and points out that ‘if you watch closely you can probably tell that he is in some discomfort. He is walking the walk of a constipated man.’ The US Ambassador to Pakistan, Arnold Raphel, is described as one ‘whose shiny bald head and carefully groomed moustache give him the air of a respectable homosexual businessman from small-town America.’

Hanif describes places, people, incidents, happenings in a way that puts them all in line with the main plot and everything seems very connected. Even the Kaaba is described to suit the mood of the novel and the state of mind of the General who is soon going to meet his end.

The door opened and nothing happened. There was nobody ambushing them. There was nobody welcoming him either.

The room was empty.

There were no flashes of divine light, no thunder, the walls of the room were black and without a single inscription. And if it hadn’t been for General Zia’s choked voice seeking forgiveness, it would have been a quiet room full of stale air. Allah’s house was a dark, empty room.

A good author must always project a willingness to enter the real object or person… and Hanif does it well. For instance, the partition has always been an enigma for us all, and history books tend to tell us only the dry bare facts in a couple of lines. The more dramatic texts go on and on and on about the massacre and the gore. But Hanif makes one of his own Generals tell about it:

We were travelling at a snail’s pace. I was trying my best to keep the attackers at bay. But at some point the military training just took over. I knew what my country wanted from me. I called my subedar major and told him that we would stop the train for the night prayers. I would go about two hundred yards from the train to pray. And I would come back after offering my prayer. “Do you know how long the night prayer is?” I asked him. I didn’t listen to his answer. “That’s all the time you have,” I said.

‘You see it was difficult but logical. I didn’t disobey the orders that I was given and what needed to be done was done with minimum fuss…’

Characters live in this book, not because the writer says that the general was a hard core schemer, ambitious, and a real strategic thinker… the author makes him say and do things that make his character obvious. Everybody in the novel saying or doing things and it is this joint effort of action that makes the pages move.

Different readers will like the book for different reasons. There may be a reviewer of a newspaper from the US who may harp on the timely release of this work and talk about the way the Afghan problem is dealt with or the humour in the presence of Osama in the party with the Afghan theme. There may be someone else who will appreciate the political undertones that are obvious in this work. I loved the things I have talked about and also the fact that Hanif makes all his characters talk with the contextual intelligence that they are supposed to have in real life.

For instance, Major Kiyani needs to know about the way intelligence operates in the country more than most other characters, and he does just that: ‘There are many ways of serving one’s country,’ Major Kiyani waxes philosophical, ‘but only one way to secure it. Only one.’ … and then the Major goes on to say: ‘Eliminate the risk. Tackle the enemy before it can strike. Starve it of the very oxygen it breathes.’ This is exactly the way intelligence is understood and treated in the country… and it is truth as understood by a person, which needs to be written. What Kiyani says may not be a universal truth but is certainly true to his character. This is what makes the novel stand out.

The book is a treat in all respects. You want to understand Pakistani history from the intriguingly comic perspective, read it. You want to know if Pakistani writers can be irreverent in their expression, this book shows they can. If you want to read excellent metaphorical expression, go ahead and treat yourself with this work. The descriptions are wonderful, the pace is blazing, the punches are well served… and the production smiles and attracts! Random House has done a great job.

Book details:

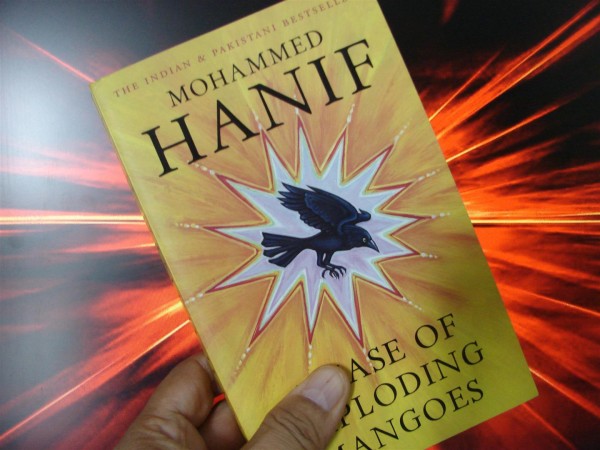

Title: A case of exploding mangoes

Author: Mohammed Hanif

Publisher: Random House India (That is, the book that I have read and reviewed)

ISBN: 9-788184-001891

Price: Rs 250/- (in 2012)

A special thanks to Rukun from Random House who sent me this book… well, Rukun, send me some more such wonderful books!

The review can also be read on the Random House India Blog.

Arvind Passey

10 August 2012