The first time that the name Ruskin Bond mysteriously entered my psyche was not when I first read his book, but during a discussion with my home tutor a while after I must have read one of his first publications. This happened sometime before my ICSE exams and in the early seventies. Rai Sahib, as my brother and I called him, was a strict disciplinarian and always wore a crisp and starched white shirt and pant and came up with unexpected questions.

‘You should read Ruskin,’ he said one evening.

‘I have read him,’ I said. He gave me a look of mild surprise, thought for a while, and asked, ‘Show me the book.’

I stood up and spent a few minutes searching before admitting that I was unable find that book right away.

‘OK, forget it,’ he said dismissively, and we went on to other tasks. Much later I happened to finally realize that he was talking of John Ruskin and not Ruskin Bond. There was a world of difference between stories written for children and complex essays on art and architecture.

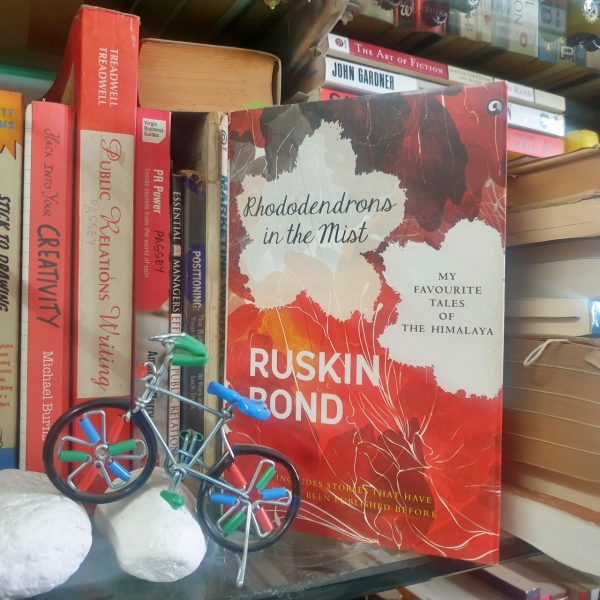

It is only when I read ‘Rhododendrons in the mist’ that the incident re-surfaced when I found that in ‘The playing fields of Simla’ even Ruskin Bond writes on how he may have got this name: ‘I think my father (Aubrey Alexander Bond) liked the works of John Ruskin, who wrote on serious subjects like art and architecture. I don’t think anyone reads him now. They’ll read me though!’ And this is a fact. I haven’t read John Ruskin as much and Ruskin Bond has risen to be one of my favourite writers over the intervening decades.

As Ruskin Bond himself writes, his stories are all about ‘trips to the plains, a crisis in my affairs, involvements with other people and their troubles’ and his writing straddles spurs and dips into valleys of human emotions, and it always seems that he has ‘lived there briefly’ and it is always as if he is telling Sushila in ‘Love is a sad song’ that he may stop loving her ‘but I will never stop loving the days I loved you’. It is those days that stay on in his memory that have found their way into the pages of his stories… and there isn’t much that the writer in him forgets and ‘…in the pastures of my mind I run my hand over your quivering mouth and crush your tender breasts. Remembered passion grows sweeter with the passing of time’ show us that his passion for story-telling is far greater than anything else in life.

This book is a compilation of stories that explore the width and depth of writing prowess of Ruskin Bond. We have the first section of fourteen dark tales of suspense, murder, and the supernatural. One meets a watchman with ‘no eyes, no ears, no features at all – not even an eyebrow’ a murderer who the writer believes will ‘turn up again one of these days’ or Rosie who gave her cyanide pill ‘a nice coating of chocolate and then mixed it up with all the little hazelnut chocolates in the tin’ that her husband took with him… diabolical stories that make you sit up and wonder how a writer of stories for children could even imagine such plots. But then this was similar to my surprise when I read the dark stories penned by another of my favourites Roald Dahl. Yes, these writers of tales for children can be quite different if they want to, I told myself and went from one story to the next and quite literally from admiring the last truck ride planned by Nathu to hearing ‘the hoof beats of Wilson’s horse as he canters across the old wooden bridge’ looking for Gulabi. Chilling stories!

The second section with another fourteen stories is quite different and one where the reader has the possibility of meeting and understanding how a writer’s mind works and why. Ruskin admits that stories have elements from a writer’s personal life though they can be sometimes placed intelligently between a lot of imaginary characters and incidents. It is in this section that I discovered that while writing his first book ‘Nine months’, the author had ‘filled three exercise books with this premature literary project, and I allowed Omar to go through them. He must have been my first reader and critic.’ Ruskin tells us that he was a student of Bishop Cotton’s that was then the premier school of India, often referred to as the ‘Eton of the East’… except that ‘there was one ‘old boy’ about whom they maintained a stolid silence – general Dyer, who had ordered the massacre at Amritsar and destroyed the trust that had been building up between Britain and India.’ It was here that he met Omar and a short conversation reveals a lot about how the writer in Ruskin finally appeared:

‘And when all the wars are done,’ I said, ‘a butterfly will still be beautiful.’

‘Did you read that somewhere?’

‘No, it just came into my head.’

‘Already you are a writer.’

‘No, I want to play hockey for India or football for Arsenal. Only winning teams!’

‘You can’t win forever. Better to be a writer.’

If you have never been to Simla, Mussorie, Barog, Kathmandu, Delhi and a few other places, the stories in the latter part of this anthology will be like a travel enthusiast eager to point out everything from a ‘steam engine chugging slowly up the steep inclines’ to watching ‘a group of children playing gulli-danda’ while sitting on a bench in Talkatora Gardens and thinking about Sushila, or standing just outside the entrance of the garden of dreams waiting for Kiran… there are conversations with love and yearning, a stoic acceptance of loneliness and solitude, and in between are incidents that stay on long after you’ve finished reading the final line in each tale. His stories aren’t travelogues but far exceed the expectations of a reader wanting to discover the soul of a place. I know this as I have trudged uphill hundreds of times with Ruskin’s stories and heard cowbells tinkling and almost imagined fairies circling around to tell me whatever it is that I wanted to believe in. Such is the power of these stories.

.

.

.

Book details:

Title: Rhododendrons in the mist

Author: Ruskin Bond

Publisher: Aleph Book Company

ISBN: 978-81-942337-6-3

.

.

.

.

.

.

Arvind Passey

15 July 2020

4 comments

radhaaariv says:

Jul 20, 2020

Such a wonderful tales you have given here. I just loved it. It’s really an informative post. One of the best posts of today, impressive. Keep sharing.

Arvind Passey says:

Aug 7, 2020

Ruskin Bond continues to be one of my favourite authors… 🙂

kisaan says:

Jul 21, 2020

Wonderful tales.Thank you for sharing ,keep posting.

Arvind Passey says:

Aug 7, 2020

Thank you… do read other book reviews as well…