Seventy-five previously published articles, stories, poems, columns, and excerpts from his books (both fiction and non-fiction) with most having ‘been expanded or updated, or both’ are powerful enough to be more than just snippets of history of things that matter to Indians. Maybe even everyone else around the world. I call these pieces more than just snippets of history because they read like a tale well told and also because ‘the telling of a tale (or a thesis) is nearly as important as the tale itself’. There were times when, despite the writing being direct, clear, and concise, I did experience a smidgen of unease until I realized that the ‘intervention of the teller’ perceives and analyses ‘the several sides to every question’ before handing them over to words and sentences on paper (or a word processor). So, this set of tales and other inclusions surely cannot be dismissed as ‘a farrago of distortions, misinterpretations, and outright lies broadcast by an unprincipled showman’ as both facts and figures come across to the reader ‘quite unselfconsciously, as a beachcomber might blow into the shells he’d picked up on a stroll along the seaside’. Let me also add here that though some of Tharoor’s conclusions may provide a willing scintilla for heated discussions on the television, they would all yet turn out to be sometimes ‘unjustifiable, but excusable’. This is because ‘the whole point about India is that this is a country for everybody, and everybody has the duty, the obligation, to work to keep it that way’.

Shashi Tharoor writes poetry as well. I had never read any of his poems yet and so I decided to go through them before reading any of the other writings… and the one that talks about humiliations endured, a neglected baby scrabbling in the dust or slumped in the mud, blazing flames and choking screams, stark ribs of skeletal cattle, drought-dried lands, and that dead-eyed refugee to finally declare:

Think of nothing.

Then you will be able

To sleep.

And yes, there are a couple of love poems as well. I must admit at this stage that reading ‘Pride, prejudice, and punditry’ by Shashi Tharoor cannot be limited to just once or be callously gifted only a cursory and disinterested page turning. It must be obvious to most readers of this review that his selection of inclusions isn’t obviously limited to politics and politicians but has also has a riveting chapter from his novel ‘Riot’ and I mention this one in particular as this is where he writes that ‘the whole point about India’ quote that is there in the first paragraph of this review. Besides his poetry, this chapter too is enough to remind readers that his writings aren’t just limited to the bureaucratizing savagery of tilting the focus of every political maneuver towards one end of the horizon of perceptions.

Shashi Tharoor has this piercing knack to express what many other writers of historical narrative find rather disconcerting and attempt to gloss over if not spreading them so thin that the real impact gets lost in circumspect mumblings that cease to be meaningful. Let’s take the word ‘Harijan’ coined by Mahatama Gandhi. Tharoor doesn’t mince his words when telling us that Ambedkar ‘rejected the word’ and used, instead, ‘the Marathi and Hindi words for the excluded (Bahishkrit), the oppressed (Dalit), and the silent (Muka) to define the outcastes’ and ‘forced India to confront the reality of discrimination’. It is with a similar forthrightness that he talks about Modi’s ‘shrewd domestic political calculation’ when he wraps himself in ‘the mantle of other distinguished Gujaratis’ and concludes that picking up Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Gandhi ‘would enable some of their lustre to rub off on him’. Well, we can all see this and the political underbelly in India as is anywhere else in the world, and this culture of poaching of USPs is a rather common occurrence. However, when a writer insists on this being an unsavory over-indulgence of just one political party, one does sit back and wonder. I believe this is one politically tinged over-indulgence that brings in an uneasy feeling. It isn’t as if the book is about bhakt-bashing because it is not. The book, let me say again, is a focused attempt to bring on the relevant facets from our recent history.

One interesting trivia is about the much-debated issue of Sonia Gandhi’s eligibility to lead the country. For those who may not be completely aware, it was Sharad Pawar, Purno Sangma, and Tariq Anwar, the three powerful Congress politicians who had raised the issue of Sonia Gandhi being ‘unfit to be prime minister because she was born in Italy’… Tharoor rushes in to say that to ‘start disqualifying Indian citizens from the privileges of Indianness is not just pernicious: it is an affront to the very premise of Indian nationalism’. This conclusion isn’t a mere emotional outburst, but the writer brings in references to Allan Octavian Hume, a Scot who founded the Indian National Congress in 1885. He also adds that the Irishwoman Annie Besant and the English Nellie Sengupta were both elected presidents of the party. Tharoor does not mince words when writing that any ‘self-appointed guardians of Indian nationalist practice’ cannot possibly overlook involved Bharatiya Sanskriti scholars from A. L. Basham to Richard Lannoy to R. C. Zaehner to Sylvain Levi, all foreigners… and that ‘there are no acid tests of birth, religion, ethnicity, or even territory that disqualify one wants to claim Indianness’. These are the sort of conclusive expressions that win the heart of readers. And readers, let me add, are no walkovers these days as they not just read to accept but know when they are being led on a wild-goose chase and will immediately stop, growl, and sometimes, even bite.

The selection of inclusions in this collection is not limited in perspective and goes way beyond dissecting personalities and enters areas that are traditionally brimming with myopic insights. Politics is one such issue. Tharoor writes what many others sweep under the carpet. He doesn’t feel inhibited in expressing his unease at the way The Wire and a few other publications have this bigoted tendency to have ‘room only for my criticism’ making readers erroneously believe that he only ‘praised him (that is, Modi) or attacked him – nothing in between’ and, therefore, in his opinion politics must ‘allow for mutual expressions of respect across political divide’. There is no need really to reduce our politics to black and white as democracy is anyway an ongoing process ‘in which there must be give and take, dialogue, and compromise among differing interests. Let us not reduce it to a game of kabaddi’. Tharoor has a rather inimitable way of embedding a surprise smile in the midst of, well, wherever he wants. I believe this is what makes the man so popular.

There are a few inclusions in the book that will indubitably do the work of a selling advert with aplomb… the article on Hinduism vs Hindutva being one of them. Now this is one piece that no one can possibly read without being impelled to immediately order a copy of his book: Why I am a Hindu. This is because four pages where Hinduism, Hindutva, nationalism, Gandhi, Modi, Savarkar, Godse, Marxism, Nehru, India, Pakistan, Vedanta, RSS, and an entire range of creative thinkers and philosophers jostle for space cannot ever be sufficient to capture the entire idea. It is the same with a few other inclusions in this collection. This article though, is brilliant even as a stand-alone piece and I particularly loved how Tharoor compares the attempt of Hindutva right’s ambiguous appropriation of Gandhi to the way the hero of the Soviet revolution is quite literally air-brushed out of historical relevance as described by Milan Kundera in his book (The Book of Laughter and Forgetting). What he is pointing out is that the ‘Mahatma’s message, spirit, and soul have vanished from today’s India. His ideals are gone. Only his glasses remain’… and that this has been done ‘by those who distort Hinduism to promote a narrow, exclusionary bigotry’. However, when Tharoor, in the same article, writes about Modi having ‘shown a decided taste for borrowed plumage’ one simply murmurs: Hey! That’s unfair because politics never has those who do not resort to this. The truth is that borrowed plumage isn’t a rarity anywhere and goes ravaging shores not even remotely connected to politics. Such references appear forced and one feels they are there because of pressures of being in the opposition. Frankly, even Tharoor loves playing a game of kabaddi once in a while!

I am surprised why I haven’t yet brought in cricket in this review… and yes, this game gets an entire section in the book. I am not complaining as one of the articles in this section does mention the utter idiocy of even considering cricket as an alternative to diplomacy. No sport can ever be a substitute for geopolitics and the ‘tendency to see India-Pakistan matches as warfare by proxy’ is equally unfortunate. The writer tells us that ‘cricket will follow successful diplomacy, not precede it’.

There aren’t many books with history as the backdrop that go around serenading the sort of range of human interactions that this book does. And so from humour to French wine to seductions and heritage, from giants among personalities to maelstroms of Indian politics, from reflections on leadership to the writerly life, and from fatalism to immortals in sports… this book is constantly looking for India all over the cultural, social, and political landscape… and yet remains secure from being set aside as some random ruminations unworthy of getting the hours that reading this will demand. All that I can say is that reading the selections is not just lead a reader towards a well-filled mind but also a well-formed one (if you can side-step his penchant for doggedly tossing every miscalculation away from the political party that he favours). Despite certain passages where a few may disagree, the book yet needs to be read again. And then possibly again.

.

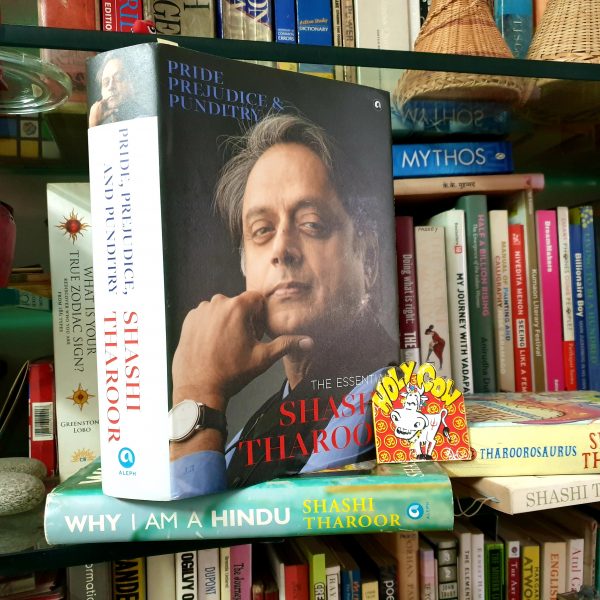

Book details:

Title: Pride, Prejudice, and Punditry

Author: Shashi Tharoor

Publisher: Aleph Book Company

ISBN: 978-93-90652-27-3

.

.

.

.

.

.

Arvind Passey

13 December 2021