Nandita Das believes that ‘actors are perceived to be much larger than they really are. But direction is something that is far more challenging and fulfilling.’ So it is only right to say that a director in a film is the emotional subtext of whatever it is that viewers finally see on the screen. The book ‘Decoding Bollywood’ has chapters on fifteen film directors and has stories based on the interactions of Sonia Golani.

‘Sounds interesting,’ I said as I casually flipped the pages of the book and stopped when I read this quote in the one where the author was talking about Nandita Das:

‘I think I wouldn’t have been able to direct if I had not written it. Because I was so close to the subject and involved in every aspect that I was able to put it all together,’ she says.’

So I decided to read this chapter first. As I went on from one director to another, I began seeing a pattern in the chapters… they were all based on a single day interaction combined with a lot of collated facts. So yes, the book does give a bird’s eye view of a director and the interactions have resulted in quotes coming straight from them. Any reader would find a director’s view on something film-related as rather interesting and insightful. I mean, had the author just stated that direction is more challenging as compared to acting, a reader would rightly have dismissed it… but the same thing coming as a response from Nandita transforms the words into a thoughtful and analytical conclusion.

Where quotes are the strength of this book based on interviews and interactions, the weak point is the lackadaisical way in which the author has planned her questioning. At some places I got a feeling that the author was more interested in gathering facts than trying to probe into the reasons for a fact happening. For instance, Nandita Das gave ‘considerable time to both dramatics and Odissi, which she had learnt for twelve years’ but a phase came when she discovered ‘nakkad natak or street theatre’ and then reached out to ‘Jana Natya Manch or JANAM’ and as a result ‘became fascinated with theatre and more importantly, an effective tool for social change’. With such a past, Nandita is bound to have a lot of things to say on street theatre and the movement that was initiated by the late Safdar Hashmi. The chapter on Nandita, however, rushes on with the chronology and leaves a reader restless. Such lapses by the interviewer are unpardonable. I mean, it is fine to focus on every film she ever acted in or every film she directed… but her opinion on vital aspects connected to street theatre could have made the chapter meaningful. But they are simply not there. However, I still loved reading the stories of these fifteen directors as the chapters still had people like Nandita saying, ‘I’ll continue to act because I believe that acting requires much less time and energy and has its own charm.’ Look at such statements by Nandita Das and then read what Farah Khan has to say on actors, and you’ll know why I found the book interesting. Farah feels that ‘actors are far more disciplined now. They report on time and are aligned to the producer and director. Every film-maker today wants to wrap up the film in time – the faster you finish, the more money you save as your office runs for lesser duration and your payables are accordingly curtailed. It’s the basic rule of any business.’

So it isn’t just direct observations on acting and direction that attracted me, but also the discovery of a strong and unflinching business instincts of Farah, the director and actor. Farah adds that actors who are still on top after years is because they are, ‘extremely disciplined, have consistently honed their talent and are well-spoken, intelligent, ambitious, and ruthless.’ Reading such things does make the entire film industry so much more human, doesn’t it? I found the chapter on Farah Khan much more incisive than many others… but then this could easily be because she is more open when she is expressing her thoughts on a subject. She doesn’t have any qualms when she says that ‘if you observe minutely, very few men from outside the industry have got a break.’ Obviously then, she would have an opinion on star-kids… but this is one thing that the author did not touch. Farah did volunteer to say that ‘it’s the recognition, the power that comes with films that draws people to it, including children who grow up in this environment. It’s the insatiable hunger for fame, for being in the public eye and not so much about the money that makes people take to films. So my guess is that my children will eventually do something related to films.’

I can understand the author steering clear of asking questions that would raise controversy of any sort… or questions that try to probe privacy… but the author could easily have asked questions that give the director’s own views on how talent is stunted because of the presence of star kids. Farah an open person and has not stopped from revealing even little intimate facts that made her progression into direction slower. She admits that ‘it was difficult for me to say, “No, I will not do your song, not do your movie.” And the years slipped by.’

As I read the book, the most fascinating thing that happened was the way even I went back in time and recollected what I thought of the film industry when I was a kid and when I was in college. Those were all opinions because of the spicy paragraphs in ‘Screen’ or ‘Filmfare’ or even the Bollywood columns in the daily newspapers. So as I read Farah talk about ‘a breed of young, twenty-something-old, women-managers accompanying actresses. Earlier, there used to be the quintessential “star mommies” who would chaperone their daughters but in retrospect, I feel they were better than these new-age managers who brainwash actresses with all kinds of nonsense…’ I also recollected all the masala gossip that used to surround the star-moms and how they expected to be pampered more than the star herself. But then Farah’s view on the new-age managers is the conclusion of a director and a business woman who has seen things as they happen on the floor of a set… and this is what gives the chapters of the book credence.

The book, therefore, carries the minds of some of the leading and known directors we have and it is interesting to read how Anurag Basu thinks… or how Mahesh Bhatt reacts to situations… or what Prakash Jha does to hone his brilliance… or what tips people like Kunal Kohli follow… or how Vipul Shah defines passion… or nod your head as you read Zoya Akhtar say: ‘I knew I wanted to do films but the films really sucked at that point. I didn’t fit in. Hindi movies made in the late Eighties and early-Nineties weren’t my kind at all!’ It is only through the pages of this book that I realised that even Zoya ‘consciously chose not to work under a single director and consolidated her experience as a freelance under several independent filmmakers like Dev Benegal and a few foreign directors.’

The only valid question that I could ask myself as I was done reading the chapters was, ‘Why only fifteen? Why not include more directors?’ Well, the only answer that I can think of is that the book would then have become a tome and would be difficult to carry. This book by Westland is surely going to be one that I will reach out for whenever I need some insight for a post that is connected to Bollywood and the films. However, I wish they stop encouraging such a low-GSM sheet as the cover… I just do not like covers curling up and lifting to reveal like a dog in heat.

.

Book Details:

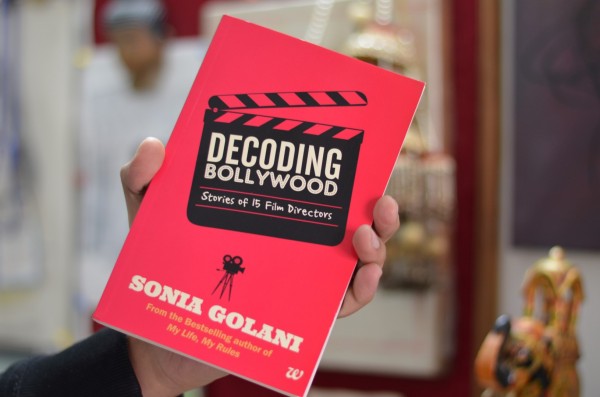

Title: Decoding Bollywood – Stories of 15 Film Directors

Author: Sonia Golani

Publisher: Westland Books

ISBN: 978-93-84030-30-8

Price: Rs 250/- (in 2015)

.

.

Decoding Bollywood – Stories of 15 Film Directors… written by Sonia Golani. Published by Westland Books

.

This book was sent by Writersmelon.

.

On Flipkart: Buy Decoding Bollywood : Stories of 15 Film Directors

On Amazon: Decoding Bollywood: Stories of 15 Film Directors

.

Arvind Passey

07 January 2015